Is CoVid-19 Higher Education’s Next Black Swan? What Does History Suggest?

Apr 08, 2020

One of the most consistent mantras of higher education is its thoughtful and methodical nature. Colleges and universities do not knee jerk. They think things through, even sometimes to a fault which is often the subject of criticism who sees higher education and its management as a parked car resistant to change and ignorance of the marketplace. Yet, this very stagnation in higher education has truly been used to its benefit, allowing these institutions to stand the test of time and be regarded worldwide as best in class.

That is why the rapid pace at which colleges and universities have reacted to the CoVid-19 pandemic is both unusual, impressive, and frightening. Most institutions have quickly moved to shutter their campuses and move their coursework to online instruction. Some have instituted extended spring breaks to prepare and develop a plan, while others have already announced that their campuses will not be reopening to in-person activities for at least the rest of the semester.

The breadth of such movements is without precedent in US higher education. As much of society are being asked to shelter in place, questions are starting to arise about what it means for the future of colleges and universities. When and how will institutions resume? Will the disruption be measured in weeks, months or years? And eventually, what will “the new normal” look like?

Theory of Black Swan Events

To provide a construct for such discussion, many educators are turning to a framework that Nassim Taleb first articulated when he published his book, The Black Swan, in 2007.

The basis of his book posits three central tenets:

- That extremely rare and hard to predict events have a disproportionately large and lasting impact on every aspect of the world.

- That it is impossible for us to calculate the downstream impact of such Black Swan events using traditional scientific methods and in real-time.

- That we, as individuals and collectively, have some type of massive psychological bias and a resulting blind spot to the uncertainty and potential massive impact that such rare events have on our future.

To be clear, the Black Swan event facing higher education because of the CoVid-19 pandemic isn’t moving their classes online — that is currently a reactionary symptom, not a revolution. For example, nearly 35% of post-secondary students enrolled in some type of online coursework already (Lederman, 2018).

In comparison, the fundamental differentiating effect of this CoVid-19 Black Swan is the vacating of entire campuses and shutting down many aspects of university work with little or no notice or planning. Furthermore, the prospective supply chain of high school seniors is also being significantly disrupted. Right in the middle of the college application, visitation, and acceptance season, institutions are in shutters from the lack of understanding of how requirements, high school graduations, and matriculation are being affected.

This is an unpredictable multi-stage disruption and end-to-end severance of normality and process.

The GI Bill and Higher Education after World War II

In hindsight, this is not the first Black Swan event in American higher education. Another one began on June 22, 1944 when Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, better known as the GI Bill of Rights.

As World War II was drawing to a close, and the memory of the poor treatment World War I veterans faced when returning home resurfaced, debate raged on how best to support these young men and women, who had lived through the Great Depression and then defended their country at its time of greatest need with a massive wartime effort.

While the bill provided for insurance benefits, and easy to obtain home financing, the most debated provision was the inclusion of an educational benefit for all veterans.

How would higher education possibly serve students who had been away from education for such a long period of time, who were many years older than their non-veteran peers, and who had real adult life experiences before arriving on campus? These soldiers simply could not be expected to succeed as higher education was not designed to support them, right? And worse, by allowing veterans admission, their participation would negatively impact the ability for more “qualified” and “traditional” students to succeed.

In 1944, James Conant, then the President of Harvard University, worried openly about the admission of such a large number of WWII veterans flooding higher education: “Unless high standards of performance can be maintained in spite of sentimental pressures and financial temptation, we may find the least capable among the war generation, instead of the most capable, flooding the facilities for advanced education in the United States.” He was not alone — the President of the University of Chicago, Robert Hutchins published an article entitled “The Threat to American Education” where he opined that colleges and universities would admit unqualified students simply to receive government funds to a disastrous end for all involved.

The topics being discussed were issues like how would married veterans fit into campus life? What about students with babies? Were there going to be enough jobs available for an increased number of marginally qualified graduates? Did these students even have the basic qualifications to attend college? And ultimately, would the noble calling of academia be reduced to rubbish to compensate for these new underperforming students?

What’s important to understand about the GI Bill as a Black Swan event, is that it was not just an influx of students that would challenge the status quo of the University, but that it would fundamentally break the model, perception, and systems that support what a University student “was” and it would do that overnight…

The downstream impact on the institutional size, capital infrastructure, personal costs, and revenue models were the true Black Swan effects that started after World War II.

The Black Swan Reality of the GI Bill

At the time of its passing, no one, even the bill’s major sponsors, envisioned more than 10% of veterans would utilize the educational benefit of the GI Bill. Those estimates were wildly incorrect. The actual data are as follows:

- 49% of WWII Veterans used GI Bill Education benefits

- 43% of Korean War Veterans used GI Bill Educational benefits

- 73% of Vietnam War Veterans used GI Bill Education benefits

Those numbers fundamentally changed the makeup of college campuses. In 1946, 1 million of the 2.5 million students enrolled in higher education were veterans. With tuition and fees covered by the government, many of these students sought out the best and most prestigious institutions in the country. 41% of students enrolled in 38 institutions, while the other 59% were distributed across the other 712 accredited institutions (Owens, 1973). By the end of 1945, President Conant, proudly proclaimed that the GI students enrolled at Harvard were “the most mature and promising students that Harvard has ever had.” At around the same time, it was reported that all of the 7,826 veterans enrolled at Columbia University in 1946 were reported as being in academic good standing.

“the greatest experiment in democratic education that the world has ever seen”

— Frank Snyder, President of Northwestern University

Historians have written of the College class of 1949 as the greatest and most successful graduating class in the history of the US higher education system. Frank Snyder, the president of Northwestern University declared it to be, “the greatest experiment in democratic education that the world has ever seen.” 70% of the graduates were veterans of the Second World War.

The lasting impact of the GI Bill Black Swan

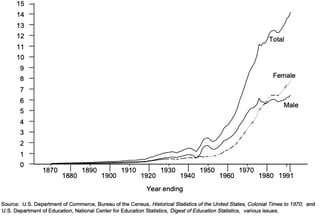

Certainly, the massive growth in college attendance was not solely because of veteran participation. But it did open the doors to the creation and expansion of other programs that changed the ability to fund a higher education experience. Scholarships, loans, and grants broadened access to nearly all high school graduates.

Besides broadening the definition of who would succeed in higher education, perhaps the more lasting legacy of the GI Bill can be broadly defined as the increase in the concept of size. Size of enrollment, campus capital infrastructure, curricular and program offerings, budgets, etc..

Prior to the GI Bill, nearly all institutions had a fairly consistent set of admission requirements — the ability to pay. While it could be argued that academic preparedness, based on high school curricula and success also factored in, students with the financial means typically found an open door to American higher education. This number slowly rose to around 1 million by the end of the Great Depression. With the US population at approximately 132 million people, this reflected less than a 1% college participation rate. By 2018, with the US population at 327 million people, college participation rates had grown to 22 million students, roughly 6.7% of the population.

In 1946, there were 750 accredited 4-year colleges and universities in the US. Today that number has ballooned to more than 2,500.

Likewise, in 1948, there were only ten institutions in the US with an enrollment of over 20,000 students; today there are 227. In that same time period, the number of institutions with over 10,000 students grew from 60 to more than 1500.

Questions for the Future

If we are going to really believe in Taleb’s three tenets and the example of the GI Bill, any speech, paper, article or blog post on the future of higher education has to be viewed with a healthy dose of skepticism. The reality is that there are way too many unknowns to predict the long term impact of CoVid-19 on Higher Education. However, it’s not too early to begin asking questions:

As seen in the above examples, the past 75 years of higher education can be characterized as a period of rapid inflation. Inflated number of financial aid programs, inflated campus infrastructure, inflated course and program offerings, inflated student size, inflated budgets, and revenue streams. And ultimately a period of “mission inflation.”

The lasting impact of this Black Swan is not something that will be measured in months or years but in decades and centuries. Some of those big questions that Higher Education will have to address are ones like:

- Should there be a differentiation of “mission” based on efficiency vs breadth?

- Will a 40% failure rate continue to be acceptable with an increasing number of students continuing to leave without a degree and rising debt?

- How will higher education manage both increasing capital costs and operational costs?

- Will increasing tuition costs that outpace inflations continue to be acceptable across the higher education landscape? Will there be some version of a return on investment calculation that will drive differentiated pricing models going forward?

In the relatively short term, Higher Education should ask:

- How will a student’s perception of their education change? Will the “on-campus” experience be devalued or re-evaluated post the CoVid-19 epidemic?

- Will students come back to campus? If so, when and who are likely to return and with what expectations?

- How will the experience of essentially 100% online tool adoption affect future in-person classrooms?

- What opportunities for return to school will be provided by government stimulus programs and new legislation post COV? Will there be GI Bill-like programs that fundamentally reshape higher education like the GI Bill?

If this truly is a Black Swan event in higher education, the one thing that is certain is that its impact will be bigger, broader, and different than we can currently imagine. History says so.

Authors:

Dr. David Palumbo, Ed.D — Chairman at Degree Analytics

Aaron Benz — CEO, Founder of Degree Analytics

Contributors:

Dr. LarryBenz, DPT, OCS, MBA, MAPP — President & CEO Confluent Health

Submit a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *